Web Essays, Magazine Articles, and Blog Posts

Hitozukuri: Japan’s Cold War education policy used religion to ‘make’ the ideal humans needed by its nascent economy. Did it work?

“For these Japanese intellectuals, The Protestant Ethic was a how-to manual.”

Is Nakamura Hikaru’s manga good for teaching about Buddhism? I investigated for Tricycle magazine.

Religious Freedom, Weapon of Choice

EXCERPT: We are reminded of the American story of religious freedom year after year. This national narrative certainly deserves careful, ongoing attention. But perhaps a more patriotic account would be characterized by humility rather than hubris. Instead of assuming that Americans naturally know what religious freedom is, we might look at moments like the Occupation of Japan when people of other nationalities have helped us think about how everyone might be free. Instead of assuming that religious freedom made the America that we know today, we might ask how Americans have made—still make—religious freedom into a weapon of choice.

What Is Shintō?

EXCERPT: Because Shintō appears essentially “Japanese,” one might assume that Japanese people intuitively know how to conduct themselves at shrines. But it is telling that many shrines display Japanese-language instructions on the “proper” protocol for venerating the kami (two bows, two claps, hold hands together while making a petition, another deep bow). Shrine priests also hang posters instructing people to bow toward the kami each time they pass through a torii gate. These initiatives suggest that Shintō priests are continually teaching Japanese people how to properly practice their own “Japanese” tradition.

Even Religious Freedom Victories Harbor Defeats

EXCERPT: [T]he relatively obscure February 1927 [Farrington v. Tokushige] decision seems like a feel-good legal win for a wrongly vilified and widely misunderstood ethnic minority. But behind this apparent victory lies a complicated story regarding American religious freedom, Buddhism, and debates over immigration that sound eerily similar to contemporary controversies about travel bans, border walls, and executive orders.

A racist image included with a 6 November 1921 Los Angeles Times op-ed by former Governor of the Territory of Hawai`i Charles J. McCarthy

Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan

EXCERPT: Secularity is anxious.

I wrote this short sentence during one of the many post-review revisions of my forthcoming book Faking Liberties: Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan. I didn’t think much of it when I wrote these three words, but I soon recognized that the sentence neatly encapsulated the main points of the book. I’ll use this post to unpack what I meant.

Domesticity & Spirituality: Kondo Is Not an Animist

EXCERPT: I was initially hesitant to join the many people churning out hot takes in response to Kondo’s show, and I remain uncertain about whether contributing to the hype is warranted or wise. But as a scholar of Japanese religions who specializes in Shintō, I couldn’t remain silent when I started to see a worrying pattern.

…

The concepts of “Shintō” and “gentle animism” that Kondo’s defenders deploy instantiate the very racism they seek to challenge. Her defenders are trading in shockingly Orientalist fantasies about timeless Asian wisdom and white ignorance, and some of them seem to have little awareness of how Japanese auto-narratives perform political work.

Teaching True Believers

EXCERPT: We do not tell our students what to believe, nor do we tell them not to believe, nor do we deny the importance of their familial traditions or personal convictions. But we help them see that it does not have to be this way or that. We encourage them to move beyond the obfuscatory personal example, and to speak about religion as a social construction or an anthropological conceit or a legal category bearing geopolitical effects. We help them see that “religion” is historically bound and culturally contingent. Together, we acknowledge that there are lots of different ways that people interact with non-obvious beings and empirically unverifiable realities. We show that ideas like karma, sin, heaven, a chosen people, and rebirth are all articles of faith and figments of the irrepressibly fecund religious imagination. We train them to not assume that everyone operates within the same imaginaries.

Training the Religious Memory

EXCERPT: There is nothing quite so touching (or quite so irritating) as having a total stranger slump against you in a deep sleep on a Tokyo train.

Like the Internet, Tokyo trains are equally intimate and anonymous. They are spaces where one encounters fellow Tokyoites in all their wacky fashion, their frenetic mobile phone gaming, their inane conversations, their drunken abandon. Tokyo trains are raucous in the evenings and eerily silent during the day. They are often uncomfortably crowded, but they are nevertheless a place to temporarily let down one’s guard. I’ve actually boarded the Yamanote circle line and ridden it all the way around the city just so I could sneak in an hour-long nap.

Corporate Profit through Buddhist Kitsch

EXCERPT: Just as some retail establishments will maintain their thermostats slightly above a comfortable temperature to encourage people to make impulse buys, and just as IKEA will wear down consumer resistance by making people physically walk past the entire store catalogue in a carefully scripted pilgrimage, this particular store lulled customers into a sense of complacent consumption by providing omnipresent physical reminders of non-acquisitiveness. The serene countenance of the Buddha blissfully absorbed in supreme unexcelled awakening said nothing at all, but his familiar visage nevertheless offered a hortatory message.

“Go ahead and buy it,” the silent statues seemed to say. “No materialism here.”

Tongue in Cheek, Just in Case

EXCERPT: Norton’s 2012 campaign was clearly driven by profit, but the ad blends the mundane need for computer security with the value-added promise of divine protection (just in case religion). Simultaneously, the ad mocks itself by subversively parodying a staid religious ceremony (tongue in cheek religion). Solemnly suited individuals kneel and bow over their computers while a priest chants an intercessory prayer (kitō) before ritual offering trays piled with USB sticks. The ancient “god power” (English phrase in the original narration) of Japan’s myriad deities both sublimates and protects the base desires of the consumers depicted in the video: the otaku (geek) with his cathectic affection for 2D dream girls; the lecherous old man with a secret pr0n stash; the flirtatious bride taking a naughty trip down memory lane; the mature woman of intrigue and innuendo; the anime music fan with her illegally downloaded tunes; the gangster who engages in shady speculation and black market deals. The need for divine protection is intimately linked to human foibles and the vices of the age; the classical Shintō preoccupation with purity and pollution is mapped onto contemporary anxieties about computer security and viral infection.

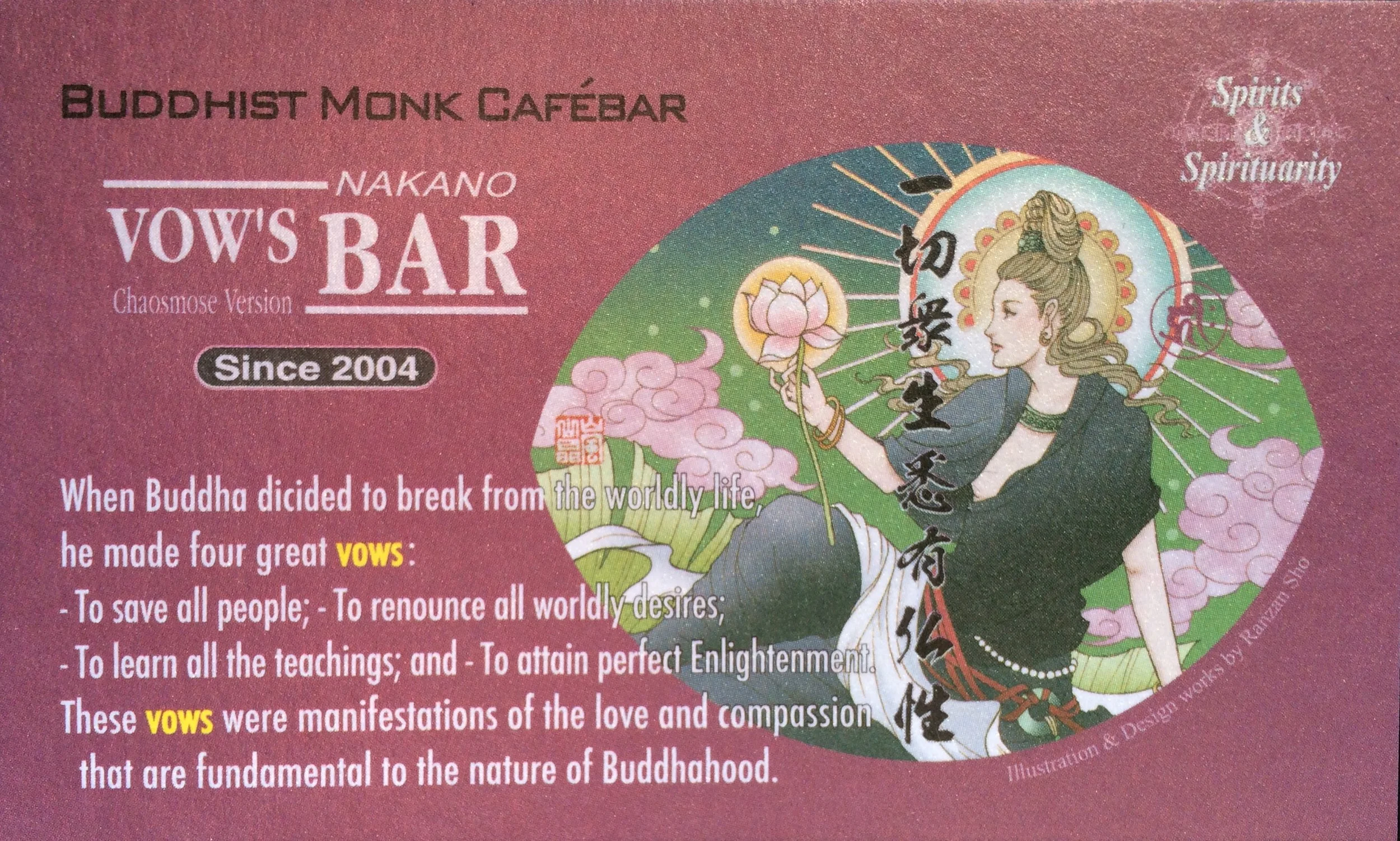

Field Notes on Drinking at a Buddhist Bar

EXCERPT: We are pretty familiar with how Tokyo’s neighborhoods reward the adventurous, so when Three and I met up for drinks in Nakano on an autumn evening in 2012, we struck out for one of the small side streets near the station instead of walking down the larger shopping arcade directly across from the station exit. We immediately found ourselves in a maze of narrow lanes barely big enough to accommodate foot traffic, let alone vehicles. Japanese tapas bars (izakaya) and noodle shops cozied up to establishments catering to the prurient interests of a heterosexual male clientele. Young women on advertising posters coquettishly eyed passersby while well-dressed hustlers inveigled groups of suited salarymen to step inside.

[...]

While people around us may have been in Nakano looking for love, our interests were relatively pedestrian. We walked deeper into the warren of restaurants and bars in search of a drink and a meal. We passed an Irish pub, a darts bar, and an establishment that offered a special “course” in which a young woman sporting a maid’s outfit would sit on a patron’s lap and clean his ears.